As a small business owner, your objectives include selling your company’s products and services, controlling expenses and making a profit. While that’s good, your small business tax rate determines how much you get to keep after taxes.

It isn’t just federal income taxes that take a bite — state and local governments also get their share. And don’t forget about payroll taxes, workers’ compensation and unemployment taxes.

Here’s what you need to know.

What Is the Small Business Tax Rate?

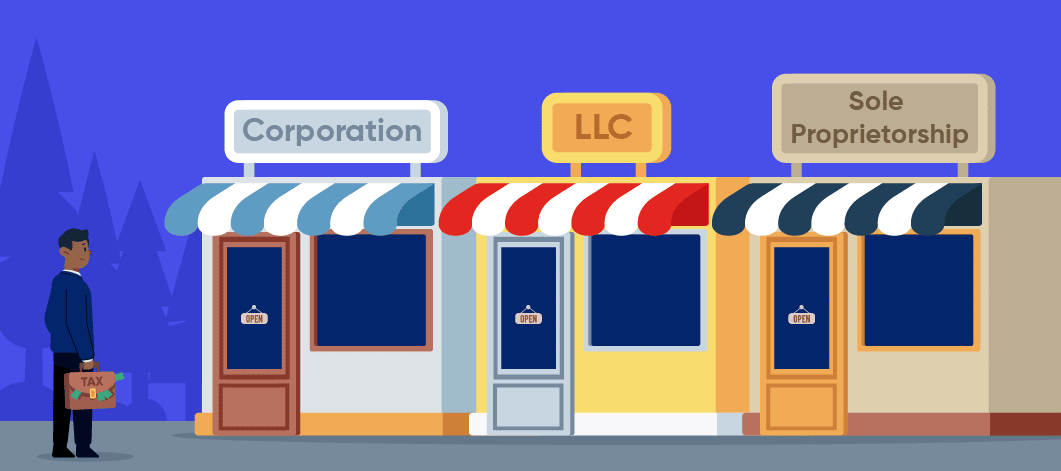

A company’s income tax rate depends on its type of legal structure. Those entities include the following:

- Sole proprietorships

- Limited liability companies (LLCs)

- Partnerships

- C corporations

- S corporations

According to the National Federation of Independent Business, 75% of small businesses are “unincorporated pass-through entities.” This means business owners pay their company’s income taxes on their personal tax returns at individual tax rates. In the U.S., personal tax rates are broken up into 7 tax brackets, currently ranging from 10%-37%.

For the 2022 tax year, the tax brackets for small business owners with pass-through entities would be the following:

- 10% for incomes of single individuals with incomes of $10,275 or less ($20,550 for married couples filing jointly)

- 12% for incomes over $10,275 ($20,550 for married couples filing jointly)

- 22% for incomes over $41,775 ($83,550 for married couples filing jointly)

- 24% for incomes over $89,075 ($178,150 for married couples filing jointly)

- 32% for incomes over $170,050 ($340,100 for married couples filing jointly)

- 35%, for incomes over $215,950 ($431,900 for married couples filing jointly)

- 37% for individual single taxpayers with incomes greater than $539,900 ($647,850 for married couples filing jointly)

Keep in mind, these are marginal income tax brackets that are progressive, meaning that the percentage of taxes for your lowest small business tax bracket is applied to the first dollars earned up to the maximum for that tier. You then move to the next level tax bracket when the income surpasses the limit on the previous tier.

In other words, using the above breakdown, if you’re single and have earned $50,000 in a year, you would be responsible for paying 10% in federal taxes on the first $10,275, 12% for the next $31,500 (the difference between $41,775 and $10,275) and 22% on your remaining earnings up to $50,000.

For example, your tax liability on $50,000 would be as follows:

10% on the first $10,275 = $1,028

12% on the next $31,500 = $3,780

22% on the last $8,225 = $1,810

Total tax liability = $6,618

In contrast to marginal tax rates, C corporations pay a flat federal tax of 21%.

Let’s look at how each type of entity is taxed in more detail.

Related: The Small Business Owner’s Guide to Deductions and Tax Write-Offs

Sole Proprietorships

Say an owner starts a business as a drywall contractor but never takes steps to incorporate or form an LLC. Businesses that have never set up an official structure with a state government will operate as sole proprietorships.

A sole proprietorship business and its activities are considered the same as the owner. That means:

- All income and losses from the business are reported on the owner’s personal income tax return.

- The business doesn’t file a separate return. The owner must pay taxes on the total earnings of the business, even if money is left in the company’s bank account to cover future expenses.

The income tax rate for a sole proprietorship depends on the individual personal tax rate of the owner. In addition, the owner of a sole proprietorship must pay all of his own self-employment taxes for Social Security and Medicare, which is 15.3% of income.

LLCs and Partnerships

While LLCs and partnerships are usually chosen to create some degree of separation of liabilities between the owners and the business, they are typically considered pass-through entities for income tax purposes.

However, LLCs do have the option of being taxed as a C corporation or an S corporation in some cases. This means that owners have to calculate the pros and cons of each alternative form and the various ways to pay their own wages and distribute dividends.

When taxed as a pass-through entity, the owners must pay their share of taxes on the company’s profits. It doesn’t make any difference whether the money stays in the business.

For example, let’s say a company makes $90,000 in profits for the year, and management wants to retain $60,000 in the company to pay for a plant expansion.

Even though the owners might receive $30,000 in distributions, they would, nevertheless, be obligated to pay taxes on the entire $90,000. In more extreme situations, the owners could end up paying more cash out in taxes than they receive in dividend distributions. These situations are known as “noncash taxable events.”

C Corporations

A C corporation is the only legal entity that pays its own income taxes. The shareholders aren’t liable for taxes on any of the company profits. However, if an owner works in the business as an employee and receives a salary, that income is taxable on the individual’s return. In addition, any dividends that stockholders receive are taxable to the recipients.

The Tax Cuts and Job Act, signed in December 2017, simplified the corporate tax code. As mentioned, the corporate tax rate for companies of all sizes is now a flat 21%. Graduated income brackets for corporations no longer exist.

A C corporation has a disadvantage in that its profits could possibly be taxed twice at the federal level. First, the corporation will pay a 21% tax on its profits. Afterward, if the company disburses any dividends, these will come out of after-tax earnings and could be subject to further taxes on the individual’s tax returns.

S Corporations

As with partnerships and sole proprietorships, S corporations are considered pass-through entities. As such, shareholders of the business must report their proportionate share of the company’s income on their personal tax return and pay taxes at their personal income tax rates.

Even though an S corporation files Form 1120S, an informational tax return, the business itself does not pay corporate taxes. This avoids the possibility of double taxation previously mentioned in C corporations.

Internal Revenue Service (IRS) rules allow S corporations to make 2 types of disbursements:

- Salaries

- Dividend distributions

However, these options lead to an interesting dilemma for the small business owner. Under S corporation rules, owners must pay self-employment taxes on their salaries. Dividends, on the other hand, aren’t subject to the self-employment tax. As a result, this interesting twist of rules creates an incentive for small business owners to draw small salaries to avoid the self-employment tax and take higher dividends.

However, the IRS is aware of this possibility and requires an owner to pay a reasonable salary for the job’s responsibilities. For example, the IRS won’t allow an owner to take a salary of $10,000 and a distribution of $50,000.

State Income Taxes

In addition to paying federal income taxes, small business owners may need to pay state income taxes depending on the state where they operate.

Business tax rates by state widely vary. A few states have additional separate taxes on LLCs and S corporations even though the owners pay business income tax on their personal state tax return.

Some states have a tax on the company’s gross receipts rather than a corporate income tax (e.g., Nevada, which also has no income tax). Typically, a business can’t take any deductions before calculating this tax.

Additionally, some states have a marginal tax rate system, while others have a flat tax system in which taxpayers are responsible for paying the same percentage on their taxes. Examples of states with a flat tax system include Colorado, Illinois, Indiana, Massachusetts, North Carolina and Pennsylvania.

Also, a few states do not have any individual income tax, such as Florida, Texas and Alaska.

Consult with a professional accountant to determine the applicable rules for the state where you operate your business.

Payment of Estimated Taxes

Regardless of the type of entity, a business must make quarterly estimated tax payments if the amount owed is more than $1,000.

C and S corporations must pay estimated taxes on a quarterly basis. Shareholders in an LLC must make quarterly tax payments on their personal income tax forms.

Sole proprietors will use IRS Form 1040-ES, Estimated Tax for Individuals to make their payments.

Other Taxes

Self-employment tax – This tax is 15.3% and covers the combined employer and employee portions of Social Security and Medicare taxes. Self-employed business owners must pay this entire amount themselves if they earn more than $400. The Social Security tax of 12.4% is imposed on the first $147,000 of net earnings, and a 2.9% Medicare tax on your entire net earnings. Furthermore, if you earn more than $200,000 ($250,000 for married couples), you’ll need to pay an additional 0.9% in Medicare taxes.

That said, a couple of income tax deductions can reduce your tax obligation: a net earnings reduction, which lowers earnings by half of the Social Security tax, as well as a deduction of half of Social Security taxes.

Additionally, according to the Social Security Administration, for 2022: “If your wages are $97,000, and you have $51,000 in net earnings from a business, you don’t pay dual Social Security taxes on earnings more than $147,000. Your employer will withhold 7.65% in Social Security and Medicare taxes on your $97,000 in earnings. You must pay 15.3% in Social Security and Medicare taxes on your first $50,000 in self-employment earnings, and 2.9% in Medicare tax on the remaining $1,000 in net earnings.”

Payroll taxes/Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA) taxes – A small business is liable for 7.65% of its employees’ gross payroll. (The payroll tax, also referred to as FICA, is a combination of 6.2% in Social Security tax and 1.45% in Medicare taxes.) Another 7.65% is deducted from the employees’ payroll checks and remitted to the IRS on a monthly or semiweekly schedule.

Federal unemployment tax (FUTA) – The amount of the unemployment tax depends on the amount of your employees’ wages. A business must file Form 940 if employee wages exceed $1,500 in a quarter.

FUTA is 6% of the first $7,000 paid to an employee. You can take a credit up to a maximum of 5.4% against this tax for any state unemployment taxes you’ve paid.

State unemployment tax (SUTA) – Each state sets its own rate for SUTA. The rate can depend on the age and size of your business, the employee turnover rate, the industry and the number of former employees who have applied for unemployment benefits.

Franchise taxes – Some states levy a franchise tax, also called a privilege tax, against businesses that operate in a state or are chartered in the state (not against franchises specifically). This tax can be determined by factors including the total assets of the business, its net worth, gross receipts and the value of the company’s capital stock. A franchise tax isn’t based on the company’s profits and must be paid whether the business makes a profit or not.